When I was co-founding Beatoven.ai, I was curious about where music as a field is headed. With streaming and social media dictating the current musical trends, I wanted a holistic view of how music has evolved over time and what could the future of music look like. On this note, let’s take a peek at this evolution of music.

Music has always been an integral part of the social functioning of humankind. We have found bone flutes from around 40 thousand years back. So, music can be assumed as one of the oldest cultural forms of expression for humans pre-dating agriculture and writing. Until not so long ago, hearing music required the presence of performing musicians but today, we can listen to more than 40 million songs just sitting in the comfort of our homes. Technology has been the biggest enabler for such a fundamental change and we will dive deep into the journey of technology within the music context.

Bone flute (Image credits— The University of Tübingen)

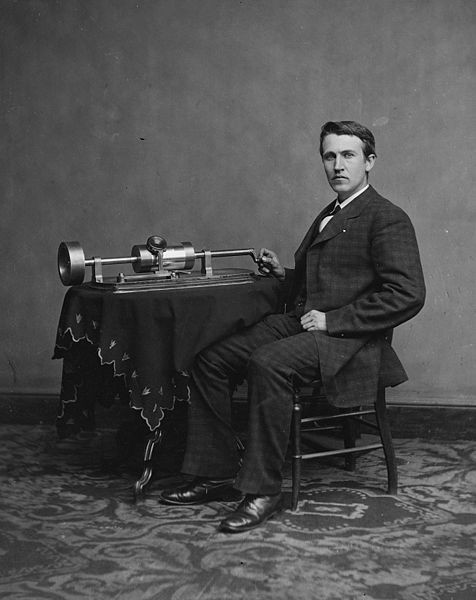

In this blog, I will cover the history starting with the invention of the phonograph by Edison in 1877 to the development of mp3 towards the end of the 20th century. I will focus on the innovation in the recording and listening technologies and how that affected the music of the day. The next blog will focus on the streaming era till present times and the last part will be about(speculative, of course) the future of music technology.

Throughout the 1870s and 80s, various loudspeaker-like devices existed, most notably on Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone (1876) and Edison’s phonograph (1877), but the true moving-coil loudspeaker, the forebear of all loudspeakers since, was invented by Oliver Lodge in 1898. Prior to this, there was no way of reproducing sound exactly. Long before sound was first recorded, music was recorded — first by written music notation, then also by mechanical devices (e.g., wind-up music boxes, in which a mechanism turns a spindle, which plucks metal tines, thus reproducing a melody). By the end of the nineteenth century, companies in the United States and England were manufacturing disc recordings of music. Prior to recordings, home consumption of all music-whether composed for keyboard or not-was by means of private piano performance.

Edison with a phonograph(Image credits— Wikimedia)

The next big innovation was that of the magnetic tape in 1928. This made sound and music not only reproducible but also alterable. This made the audio engineers’ role very crucial to the recording. Today, we hear unaltered music very rarely and that revolution began here. At the same time, Neumann also developed the first condenser microphone. The reproduction quality of these first models was quite limited, and, initially, their recommended use was the recording of monologues and famous speeches.

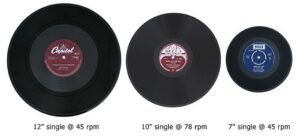

In 1930, RCA-Victor made the first vinyl long-players commercially available. They were an underground concept until 1948 when Columbia Records reintroduced their take on the format and a revolution happened. Broadcasting radios started to use this equipment, expanding its broadcasting possibilities — the live musicians’ constant presence was no longer necessary and the recording studio was born. In 1948, vinyl hit the market. Immediately, it was adopted by the consumers as their preferred medium for sound reproduction. Innumerable sizes and speeds of vinyl records were marketed and evolving along with technology and commercial interests. The first records were 7-inch discs and were to be played at 78 rpm’s, which provided less than four minutes per side, leading to the single compact format with one piece of music on each side and within this duration margin. Moreover, vinyl grooves imposed some serious volume restrictions on bass frequencies, for they caused needle jumps if they were too loud. The form and sound of pop and rock music that we’ve known through the years were strongly influenced by these limitations.

Image credits — Wikimedia

In 1946, Webster-Chicago also manufactured a ‘Wire Recorder’ which could be used in the comfort of your own home.

On the reproduction side, Bell Labs used a 1937 demonstration film to show off their two-channel innovation, which split up multiple tracks from a single source recording. Three years later, Disney seized on the technology and released ‘Fantasia’, the first commercial studio film amplified by high-fidelity stereo sound.

The recording and distribution process lay in the hands of a new kind of company that, structuring the musical industry, controlled the production and consumption cycles during the second half of the 20th century: the record company or the labels.

In 1957, American guitar player Les Paul modified a magnetic tape recorder to create the first multiple-layer recorder, making it possible to add new instruments onto the same tape roll, playing one by one. As there was only one recording track, a recording mistake would ruin the former work and the whole process would have to be restarted. Soon, multi-track recorders would come into the picture and musicians could record multiple tracks at different times introducing additional overdubs and layers.

Tape Recorder(Image credits— Wikimedia)

This evolution was slow and led by various independent studios worldwide. All the records from the beginning of The Beatles’ career to Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, in 1967, was recorded using only four tracks of a magnetic tape. In the following decade, the tapes evolved to eight, sixteen, and up to twenty-four tracks.

Since the beginning, record companies created a closed system for their business. Composers were paid to write new musical pieces. These creations were recorded at the company’s own studio by a hired artist, who was made popular by the radio, which boosted sales, and generated huge profits for his/her employer. Independent artists always existed, but their sphere of influence was naturally smaller. To make their music cross the planet and influence other cultures, it was necessary to be part of that closed circuit of contract, recording, marketing, and massive sales — at least until technology made it possible for performers to exist outside this entire scheme.

The next big innovation came in the form of a cassette tape. By 1963, radio had become ubiquitous and kids were hooked to rock and pop music of the time. At this time, Phillips consolidated the bulky reel-to-reel and revealed the first cassette tape at a 1963 fair in Berlin. Cassettes would become the chief mode for distributing albums alongside vinyl and CDs before the digital revolution, not to mention a beloved means of self-expression (via mixtapes) for millions of heart-aching teens.

The capitalist world had been consuming a mix of global and local hits since the 1950s. At the end of the 1970s, however, the industry, concerned by the drop in vinyl records sales, had to reinvent itself. One of the main factors that saved record companies at that time was another technological innovation.

Up until 1982, storing and reproducing sounds was essentially made in an analogical manner, by physically printing audio through electromagnetic and mechanical means. In that year, a new technology, the compact disc (CD), introduced digitally represented information. During the 1980s and 1990s, the digital format multiplied industry profits due to decreasing reproduction costs and a booming market for pop music.

A little before the CD was released, recording and manipulating audio were still essentially analog comprising magnetic tape, valves, and transistors. Since the end of the 1970s, however, digital equipment started getting increasingly more space in the studios: processors, board, and recording machines started to be converted to the new technology. In the analog studio, the microphone converted the picked-up sound into an electric wave, which ran along wires and equipment. It was altered and manipulated by the soundboard, processors, and, finally, recorded onto a magnetic tape. In the digital world, the sound was represented by a sequence of numbers that described the audio.

Also, a very impactful invention was that of “The Walkman’’ in 1979 by Sony. It was a convenient, fashionable way to make an already portable innovation even more portable. The Walkman represented a true synergy of music tech, for it wouldn’t have been possible without Phillips’ cassette tape or Nathaniel Baldwin’s headphones.

Original Sony Walkman(Image credits — Wikimedia)

Developed in the late 1980s and standardized in the early 1990s, MP3 was first pronounced dead in 1995 and nearly abandoned as a technology. Mp3 is an algorithm that drastically changes the audio file size, reducing it to up to 8% of the original size. Much of this reduction only results from an intelligent way of describing the file content, but, depending on the parameters used, the files it generates have a much lower audio quality. It was deemed commercially unsuccessful despite heavy investment from the Fraunhofer institute and a decade’s development by the project’s leader Karlheinz Brandenburg. It was the victim of a format war, led by Dutch manufacturer Philips.

Fraunhofer’s MP3 was consistently overlooked in the early 1990s by the MPEG standards group in favour of Philips’ MP2. The MP3 format only found early commercial success in the sports broadcast market, with the compressed digital audio saving broadcasters thousands in satellite transmission costs. So deeply unpopular was MP3 in commercial music applications that the developers effectively gave it away for free. At the same time, the increasing availability of personal computers and the World Wide Web also ushered in file sharing websites, built around the distribution of pirated content, and peer-to-peer networks like Napster revived the interest in mp3.

In 1995, the quality loss became a lot less important for the listeners than the capacity of exchanging music online. This brought an unprecedented change in listening habits across the world, music essentially just became a digital asset and considered to be free by many. The rise of peer-to-peer file-sharing networks, most famously Napster, meant that now anyone with a computer and internet connection could access another person’s entire music collection. A single file could be copied by thousands, all at the same time.

This seismic shift would lead us into our next blog where I will cover how the music industry tried its best to get out of this age of piracy and ushered in an era of streaming.

We at Beatoven.ai want to be at the forefront in defining the trends for the future of music composition for video and podcast content. Do check us out and get in touch by filling in your details on our website.